Pause and pondr

WHAT IS BLACK AMERICAN SIGN LANGUAGE?

Black American Sign Language, a unique dialect born out of segregation and exclusion, reflects the nuances, solidarity and culture of the African American deaf community.

DID YOU KNOW?

Only 44.8% of deaf African Americans and 43.6% of deaf Native Americans are in the labor force, compared to 59% of deaf Whites.

Source: Deaf People and Employment in the United States 2019

WHAT YOU’LL LEARN

Describe the history and features of Black American Sign Language

Reflect on how languages evolve and thrive, even within the context of oppression

What are the nuances of BASL?

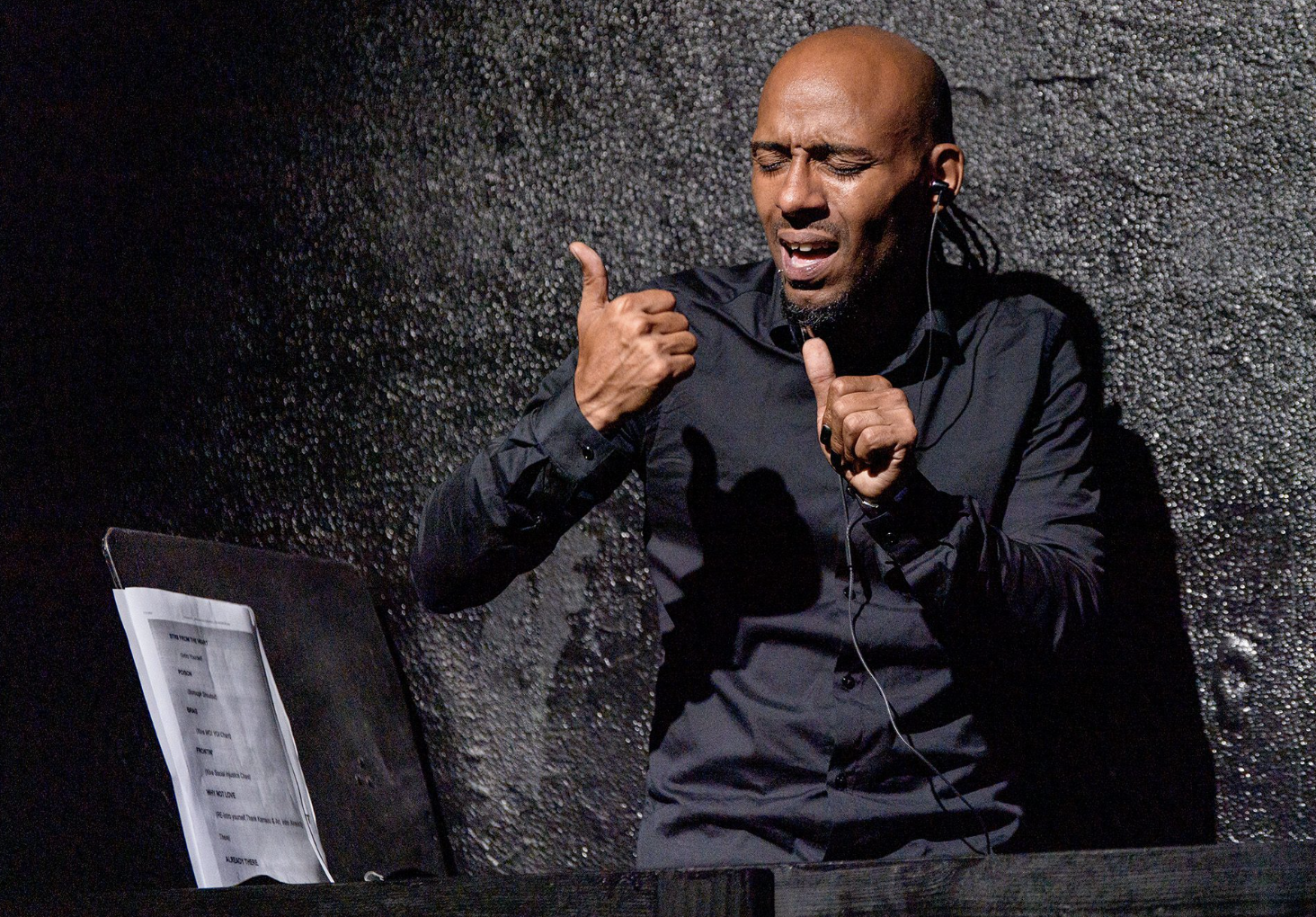

BASL is a dialect of American Sign Language used primarily by Black deaf communities across the United States. Members of the BASL community sometimes describe it as a language with swagger or layers — one that encapsulates the nuances of Black deaf culture and is used by Black deaf people engaging in conversations with families and friends in social and other nonprofessional settings.

“If you talk about the Black style of signing … I usually do that with my Black deaf friends in whatever settings,” said Joseph Hill, an associate professor at the National Technical Institute for the Deaf at Rochester Institute of Technology and a co-author of “The Hidden Treasures of Black ASL: Its History and Structure.”

There are several key distinctive features of BASL, which include vocabulary differences, use of repetition, two-handed versus one-handed signs, and size of signing space. Other differences include facial expressions and directional movement.

What is the genesis of BASL?

Originating from the 17th- to mid-20th centuries, BASL has its roots in discrimination and segregation experienced by Black Americans.

Benro Ogunyipe, the former president of National Black Deaf Advocates, has said Black deaf people were subjected to “double prejudice” from members of both Black and white society. He writes that historically the concerns of Black deaf communities were not the focus of Black advocacy organizations, which were solely focused on civil rights issues. Meanwhile, predominantly white deaf organizations prohibited Black people from joining their groups.

The National Association of the Deaf, for instance, did not accept Black members until 1965. Gallaudet University in Washington, D.C., whose student body consists of the deaf and hard of hearing, had its first Black graduate in 1954 — 90 years after the institution was founded. In the South, schools for Black deaf people were not created until after the Civil War. (However, the first permanent institution for the deaf, now known as the American School for the Deaf that opened in 1817 in Hartford, Connecticut, did start accepting Black students as early as 1825.)

“It didn’t matter if the Black and white schools for the deaf were in the same town … or a couple hundred miles apart … the students were not legally allowed to be in the same space for around 100 years,” Hill explained. “So of course, their languages were different.” And the different vocabularies, signs and ways of communicating were the precursors to BASL.

How is BASL being recognized and preserved?

From mainstream media coverage to posts by social media influencers such as TikTok star Nakia Smith (who is Black and deaf), BASL is gaining more national attention in recent years.

“Signing Black in America,” the first documentary about BASL that aired on PBS stations nationwide, was created after the release of “Talking Black in America,” an Emmy-winning feature-length documentary that examines the impact of African American English on American language and culture. When “Talking Black in America” premiered in 2017 at the University of Kentucky in Lexington, the film’s executive producer and linguistics professor Walt Wolfram said a deaf student in the audience asked him, “Why don’t you do something like this for Black ASL?”

Wolfram, who is now the William C. Friday Distinguished University Professor at North Carolina State University in Raleigh, took the student’s words to heart. “There are very few documentaries on ASL to begin with and absolutely none (at that time) on BASL. Our role is to educate people about ASL and the fact that it’s not a universal sign language,” he said.

Even though BASL has gained prominence over the years, more can be done — by increasing the number of teachers teaching BASL and including it in ASL and deaf studies programs in secondary and postsecondary settings, Hill said.

“We don’t have teachers who are proficient in Black ASL to teach it,” he said. “Institutional barriers are the factor that explains the low number of Black deaf teachers of ASL and the lack of diversity in ASL curriculum.”

Hill’s next BASL-related project will be a study on Black deaf multigenerational families.

For preservationists, the more BASL is studied and recognized widely, the more it’s likely the language is not forgotten — and the more likely that equity and inclusion for members of the Black deaf community are reinforced.

If you’d like to learn more about BASL, visit Gallaudet University’s Black ASL Project, (part of the university’s Center for Black Studies), where you can read about the history, variations and other aspects of the language.

You can also visit the website of the National Black Deaf Advocates, the advocacy and civil rights organization that aims to promote leadership development, economic and educational opportunities and social equity, and seeks to protect the general health and welfare of Black deaf and hard of hearing Americans. Find your closest chapter here.

Pondr This

Do you have any experiences with ASL or BASL?

How have languages shaped your own life?

Do you think cultural preservation and knowledge of languages is important? Why, or why not?

FOR LEADERS

Do you know what different languages your employees speak?

How does your workplace support or not support the use of multiple languages?

How do you think your employees speak and talk outside of work? How can the use of those languages be promoted in your workplace?

Explore The Stories

Black American Sign Language: A toolkit

Racial awakening leads to organizational introspection, action

-

Emiene is an avid storyteller, journalist and editor creating content on print and digital platforms. She has been published in the NAACP’s Crisis Magazine, North Carolina’s Our State magazine, and The Charlotte Observer.

Sign language with swagger

-

Angie Chatman is a writer, editor and storyteller. She focuses on the intersection of race and social justice in the business, tech, education and food sectors. She lives in Boston, Massachusetts, with her family, including rescue dog Lizzie.

Topic in Review

We look at the historical roots of Black American Sign Language and the growing recognition of its importance.

Continue Your Journey

One common misconception about sign language is that it’s a universal language. But countries have their own sign language around the world and there are dialects to account for regional differences, not to mention other variations tied to race, class and gender. There’s an estimated more than 300 distinct sign languages globally.

BASL, like all languages, is still continuously developing and changing and has a long history that has shaped the spectrum of features, signs and styles that vary for each signer in different situations.

To learn more about BASL, visit the Black ASL Project. Sponsored in part by Gallaudet University’s Department of Linguistics and Department of ASL and Deaf Studies, the project aims to educate the public about the linguistic features of BASL.

Further readings about Black ASL recommended by the project include:

Hairston, E., & Smith, L. “Black and Deaf in America: Are We That Different?” TJ Publishers, 1983: This book gives an in-depth look historically at the issues the Black Deaf community faces regarding employment and educational opportunities.

McCaskill, C., et al. “The Hidden Treasure of Black ASL: Its History and Structure,” Gallaudet University Press, 2011: This pioneering work by scholar and Deaf advocate Carolyn McCaskill is the first sociohistorical and linguistic study of the language.

Stead Sellers, F. “How America developed two sign languages — one white, one black,”

The Washington Post, Feb, 21, 2020: This article delves into the development of BASL through the shared identity and history of the Black Deaf community.

You can also watch Vice News' report last March, "Reclaiming Black American Sign Language," which provides additional historical perspective as well as insight into a current focus on preserving BASL. The Talking Black in America Project out of NC State has also developed educational resources for its documentary series, including its groundbreaking “Signing Black in America.” Their discussion guide can be found here.